A task force counting Amazon, Cisco, and the FBI among its members has proposed a framework to solve one of cybersecurity’s biggest problems. Good luck.

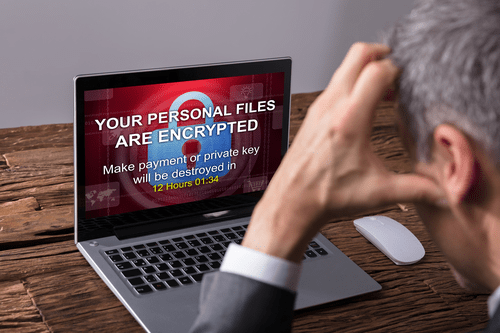

SCHOOLS, HOSPITALS, THE City of Atlanta. Garmin, Acer, the Washington, DC, police. At this point, no one is safe from the scourge of ransomware. Over the past few years, skyrocketing ransom demands and indiscriminate targeting have escalated with no relief. Today a recently formed public-private partnership is taking the first steps toward a coordinated response.

The comprehensive framework, overseen by the Institute for Security and Technology’s Ransomware Task Force, proposes a more aggressive public-private response to ransomware rather than the historically piecemeal approach. Launched in December, the task force counts Amazon Web Services, Cisco, and Microsoft among its members, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and the United Kingdom National Crime agency. Drawing from the recommendations of cybersecurity firms, incident responders, nonprofits, government agencies, and academics, the report calls on the public and private sectors to improve defenses, develop response plans, strengthen and expand international law enforcement collaboration, and regulate cryptocurrencies.

Specifics will matter, though, as will the level of buy-in from government bodies that can effect change. The US Department of Justice recently formed a ransomware-specific task force, and the Department of Homeland Security announced in February that it would expand its efforts to combat ransomware. But those agencies don’t make policy, and the United States has struggled recently to produce a coordinated response to ransomware.

“We need to start treating these issues as core national security and economic security issues, and not as little boutique issues,” says Chris Painter, a former Justice Department and White House cybersecurity official who contributed to the report as president of the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise Foundation. “I’m hopeful that we’re getting there, but it’s always been an uphill battle for us in the cyber realm trying to get people’s attention for these tremendous issues.”

Thursday’s report extensively maps the threat posed by ransomware actors and actions that could minimize the danger. Law enforcement faces an array of jurisdictional issues in tracking ransomware gangs; the framework discusses how the US could broker diplomatic relationships to involve more countries in ransomware response and attempt to engage those that have historically acted as safe havens for ransomware groups.

“If we’re going after the countries that are not just turning a blind eye but are actively endorsing this, it’ll pay dividends in addressing cybercrime far beyond ransomware,” Painter says. He admits that it won’t be easy, though. “Russia is always a tough one,” he says.

Some researchers are cautiously optimistic that the recommendations could lead to increased collaboration between public and private organizations if enacted. “Larger task forces can be effective,” says Crane Hassold, senior director of threat research at the email security firm Agari. “The benefit of bringing the private sector into a task force is that we generally have a better understanding of the scale of the problem because we see so much more of it daily. Meanwhile, the public sector is better at taking down smaller components of the cyberattack chain in a more surgical manner.”

The question, though, is whether the IST Ransomware Task Force and new US federal government organizations can translate the new framework into action. The report recommends the creation of an interagency working group led by the National Security Council, an internal US government joint ransomware task force, and an industry-led ransomware threat hub, all overseen and coordinated by the White House.

“This requires decisive action at multiple levels,” says Brett Callow, a threat analyst at the antivirus firm Emsisoft. “Meanwhile, frameworks are all well and good, but getting organizations to implement them is an entirely different matter. There are many areas where improvements can be made, but they will not be overnight fixes. It’ll be a long, hard haul.”

Callow argues that strict prohibitions on ransomware payments could be the closest thing to a panacea. If ransomware actors couldn’t make money from the attacks, there would be no incentive to continue.

That solution, though, comes with years of baggage, especially given that critical organizations like hospitals and local governments may want the option of paying if dragging out an incident could disrupt essential services or even endanger human life. The framework stops short of taking a stand on whether targets should be allowed to pay, but it advocates expanding resources, so victims have alternatives.

While a framework offers a potential path forward, it does little to help with the urgency felt by ransomware victims today. Earlier this week, the ransomware gang Babuk threatened to leak 250 gigabytes of data stolen from the Washington Metropolitan Police Department—including information that could endanger police informants. No amount of recommendations will defuse that situation or the countless others that play out daily around the world.

Still, an ambitious, long-odds proposal is better than none at all. And the incentive to address the ransomware mess will only become more significant with each new hack.