People who gamble on sports generally bet all their money on one team. If their team wins, they reap the rewards. And if their team loses? They lose it all. But with investing, you don’t have to bet on only one team—you can divide your money among different types of assets. This is what we call asset allocation. Done right, asset allocation safeguards your money and maximizes its growth potential, regardless of which team is winning in markets.

Asset Allocation Definition

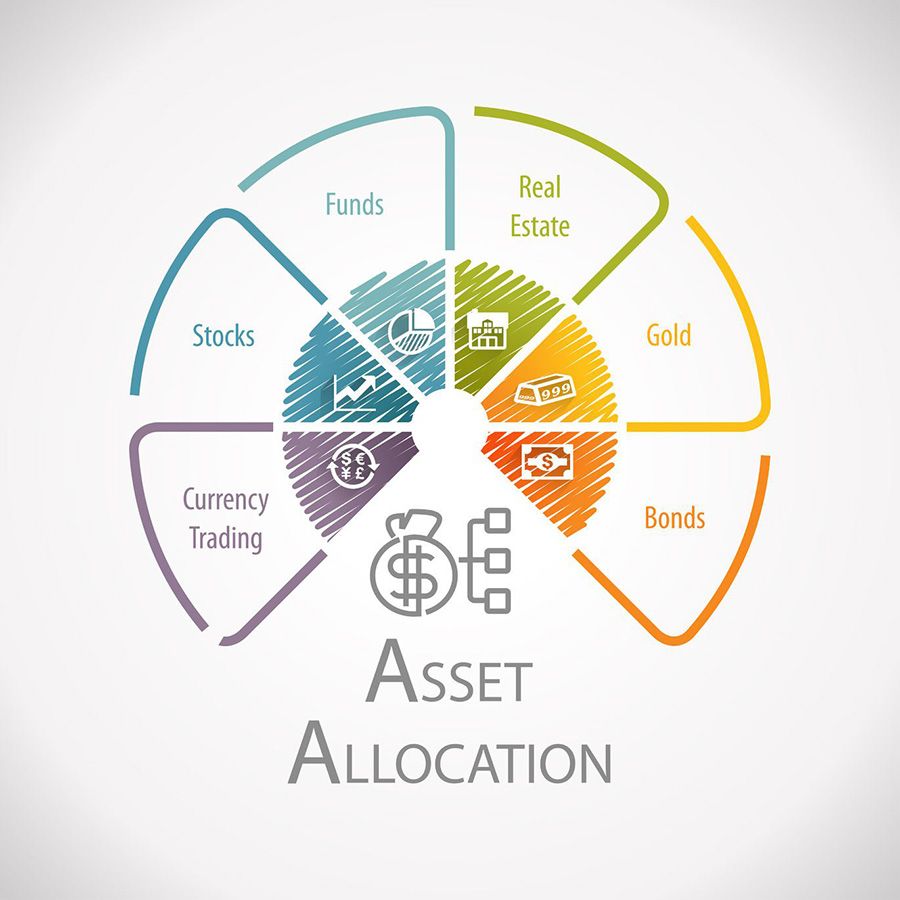

Asset allocation divides the money in your investment portfolio among stocks, bonds, and cash. The goal is to align your asset allocation with your tolerance for risk and time horizon. The three main asset classes are:

- Stocks. Historically stocks have offered the highest rates of return. Stocks are generally considered riskier or aggressive assets.

- Bonds. Bonds have historically provided lower rates of return than stocks. Bonds are typically considered safer or conservative assets.

- Cash and cash-like assets. While you don’t typically think of cash as an investment, cash equivalents like savings accounts, money market accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), cash management accounts, treasury bills, and money market mutual funds are all ways that investors can enjoy potential upside with deficient levels of risk.

You’re probably already familiar with thinking about your investment portfolio in terms of stocks and bonds. But cash and cash-like assets are also essential pieces of the asset allocation puzzle. These highly liquid assets offer the lowest rate of return of all asset classes but also a shallow risk, making them the most conservative (and stable) investment asset.

You can buy individual stocks or bonds to get your desired asset allocation. But new investors should stick to exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and mutual funds. There are countless funds to choose from, each of which owns an extensive selection of stocks or bonds based on a particular investing strategy (like matching the performance of the S&P 500) or asset type (like short-term municipal bonds or long-term corporate bonds).

How Does Asset Allocation Work?

Asset allocation divides your investments among stocks, bonds, and cash. The relative proportion of each depends on your time horizon—how long before you need the money—and risk tolerance—or how well you can tolerate losing money in the short term for the prospect of more significant gains over the long term.

Asset Allocation & Time Horizon

Your time horizon is a fancy way of asking when you’ll need the money you’re investing. If it’s January and you’re investing for a vacation in June, you have a short time horizon. If it’s 2020 and you plan to retire in 2050, you have a long time horizon.

With short time horizons, a sudden market decline could put a severe dent in your investments and prevent you from recouping losses. For a short time horizon, experts recommend that your asset allocation consist primarily of cash assets, like savings or money market accounts, CDs, or even certain high-quality bonds. You don’t earn very much, but the risks are very low, and you won’t lose the money you need to go to Aruba.

With longer time horizons, you may have many years or decades before you need your money. This allows you to take on substantially more risk. You may opt for a higher allocation of stocks or equity funds, which offer more potential for growth. If your initial investment grows substantially, you’ll need less of your own money to reach your investment goals.

With aggressive, higher-risk allocations, your account value may fall more in the short term. But because you have a far-off deadline, you can wait for the market to recover and grow, which historically it has after every downturn, even if it hasn’t done so immediately.

After each recession since 1920, it has taken the stock market an average of 3.1 years to reach pre-recession highs, accounting for inflation and dividends. Even considering bad years, the S&P 500 has seen average annual returns of about 10% over the last century. You’re never sure when a recession or dip will arrive. As your investing timeline shrinks, you probably want to make your asset allocation more conservative (bonds or cash).

For goals that have less well-defined timelines or more flexibility—you might want to take a trip to Australia at some point in the next five years but don’t have a set date in mind—you can take on more risk if you’re willing to delay things until your money recovers or you’re okay with taking a loss.

Asset Allocation & Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance is how much of your investment you’re willing to lose for the chance of achieving a greater rate of return. How much risk you can handle is a profoundly personal decision.

If you’re an investor who’s not comfortable with big market swings, even if you understand that they’re a normal part of the financial cycle, you probably have lower risk tolerance. If you can take those market swings in stride and know that you’re investing for the long term, your risk tolerance is probably high.

Risk tolerance influences asset allocation by determining the proportion of aggressive and conservative investments you have. This simply means what percentage of stocks versus bonds and cash you hold.

Both high and low-risk tolerances will lose money at some point in the investment cycle—even if it’s only to inflation—but how big those swings are will vary based on the risk of the asset allocation you choose.

Even if you’re comfortable with many risks, your investing timeline may influence you to hold a more conservative portfolio. If you’re only a few years from retirement, you might switch to a bond- and fixed-income-heavy portfolio to help retain the money you’ve built up over your lifetime.

Why Is Asset Allocation Important?

Choosing the proper asset allocation maximizes your returns relative to your risk tolerance. This means it helps you get the highest payoff for the amount of money you’re willing to risk in the market. You accomplish this balance through the same kind of diversification mutual funds, and ETFs provide—except on a much broader level.

Buying a mutual fund or an ETF may provide exposure to hundreds if not thousands of stocks or bonds, but they’re often the same type of asset. A stock ETF offers diversification in stocks, but you’re still undiversified in asset allocation. If one of the companies in an ETF goes bankrupt, your money is probably safe. But if the whole stock market crashes, so do your savings.

To diversify your asset allocation, split your money between a stock ETF and a bond ETF. This helps protect your money because, historically, stocks and bonds have an inverse relationship: When one is up, the other is generally down. Striking a balance between the two can position your portfolio to retain value and grow no matter what markets do.