What Is Say’s Law of Markets?

Say’s Law of Markets comes from chapter XV, “Of the Demand or Market for Products,” of French economist Jean-Baptiste Say’s 1803 book, Treatise on Political Economy, Or, The Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth. It is a classical economic theory that says that the income generated by past production and sale of goods is the source of spending that creates demand to purchase current production. Modern economists have developed varying views and alternative versions of Say’s Law.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Say’s Law of Markets is a theory from classical economics arguing that the ability to purchase something depends on the ability to produce and generate income.

- Say reasoned that to have the means to buy, a buyer must first have produced something to sell. Thus, the source of demand is production, not money itself.

- Say’s Law implies that production is the key to economic growth and prosperity, and government policy should encourage (but not control) production rather than promote consumption.

Understanding Say’s Law of Markets

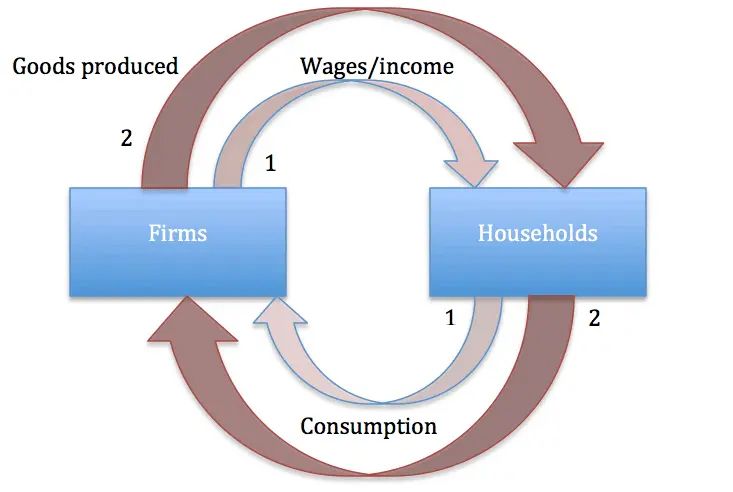

Say’s Law of Markets was developed in 1803 by the French classical economist and journalist Jean-Baptiste Say. Say was influential because his theories address how society creates wealth and the nature of the economic activity. To have the means to buy, a buyer must first have sold something, Say reasoned. So, the source of demand is before producing and selling goods for money, not money itself. In other words, a person’s ability to demand goods or services from others is predicated on the income produced by that person’s past acts of production.

Important:

Say’s Law says that a buyer’s ability to buy is based on the buyer’s successful past production for the marketplace.

Say’s Law ran counter to the mercantilist view that money is the source of wealth. Under Say’s Law, money functions solely as a medium to exchange the value of previously produced goods for new goods as they are produced and brought to market, which by their sale then, in turn, make money income that fuels demand to subsequently purchase other goods in an ongoing process of production and indirect exchange. To Say, money was simply a means to transfer real economic interests, not an end.

According to Say’s Law, a demand deficiency for good in the present can occur from a failure to produce other interests (which would otherwise have sold for sufficient income to purchase the new good), rather than from a shortage of money. Say went on to state that such deficiencies in producing some goods would, under normal circumstances, be relieved before long by the inducement of profits to be made in producing the goods that are in short supply.

However, he pointed out that the scarcity of some goods and glut of others can persist when the breakdown in production is perpetuated by ongoing natural disasters or (more often) government interference. Say’s Law supports the view that governments should not interfere with the free market and should adopt laissez-faire economics.

Implications of Say’s Law of Markets

Say drew four conclusions from his argument.

- The greater the number of producers and the variety of products in an economy, the more prosperous it will be. Conversely, those members of a society who consume and do not produce will be a drag on the economy.

- The success of one producer or industry will benefit other producers and industries whose output they subsequently purchase, and businesses will be more successful when they locate near or trade with other successful companies. This also means that government policy encouraging production, investment, and prosperity in neighboring countries will also redound to benefit the domestic economy.

- The importation of goods benefits the domestic economy even at a trade deficit.

- The encouragement of consumption is not beneficial but harmful to the economy. Over time, the production and accumulation of goods constitute prosperity; consuming without producing eats away the wealth and prosperity of an economy. Good economic policy should encourage industry and productive activity while leaving the specific direction of which goods to deliver and how up to investors, entrepreneurs, and workers in accord with market incentives.

Say’s Law thus contradicted the popular mercantilist view that money is the source of wealth, that the economic interests of industries and countries conflict with one another, and that imports harm an economy.

Later, Economists and Say’s Law

Say’s Law still lives on in modern neoclassical economic models and has influenced supply-side economists. Supply-side economists believe that tax breaks for businesses and other policies intended to spur production without distorting financial processes are the best prescription for economic policy, in agreement with the implications of Say’s Law.

Austrian economists also hold to Say’s Law. Say’s recognition of production and exchange as processes occurring over time, focus on different types of goods as opposed to aggregates, emphasis on the role of the entrepreneur to coordinate markets, and conclusion that persistent downturns in economic activity are usually the result of government intervention are all remarkably consistent with Austrian theory.

Say’s Law was later (and misleadingly) summarized by economist John Maynard Keynes in his 1936 book, General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, in the famous phrase, “supply creates its demand.” However, Say himself never used that phrase. Keynes rewrote Say’s Law, then argued against his new version to develop his macroeconomic theories.

Keynes reinterpreted Say’s Law as a statement about macroeconomic aggregate production and spending, disregarding Say’s clear and consistent emphasis on showing and exchanging various particular goods against one another. Keynes then concluded that the Great Depression appeared to overturn Say’s Law. Keynes’ revision of Say’s Law led him to argue that an overall glut of production and deficiency of demand had occurred and that economies could experience crises that market forces could not correct.

Keynesian economics argues for economic policy prescriptions that are directly contrary to the implications of Say’s Law. Keynesians recommend that governments intervene to stimulate demand—through expansionary fiscal policy and money printing—because people hoard cash during hard times and liquidity traps.