What you need to know about these financial statements

What Is a Balance Sheet?

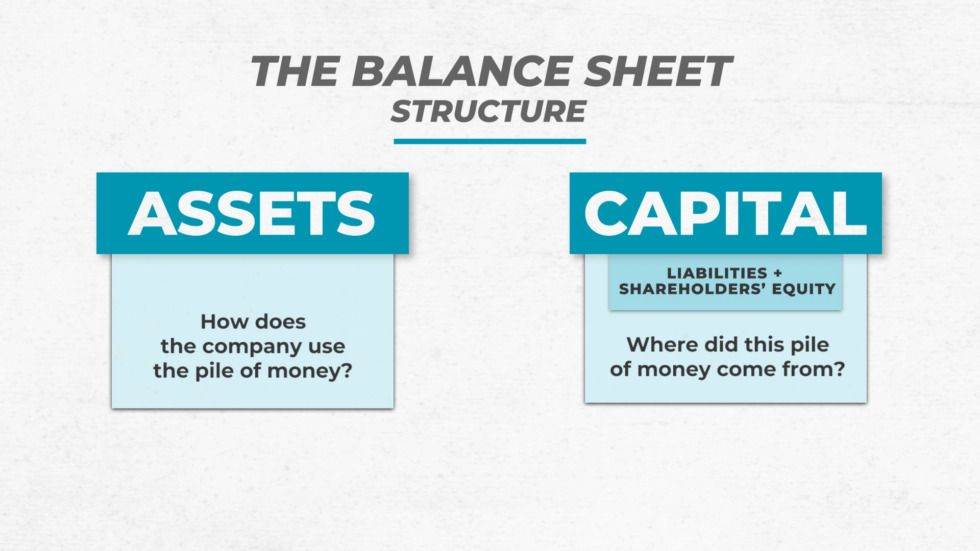

The term balance sheet refers to a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity at a specific time. Balance sheets provide the basis for computing rates of return for investors and evaluating a company’s capital structure.

In short, the balance sheet is a financial statement that provides a snapshot of what a company owns and owes and the amount invested by shareholders. Balance sheets can be used with other important financial information to conduct fundamental analysis or calculate financial ratios.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- A balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity.

- The balance sheet is one of the three core financial statements used to evaluate a business.

- It provides a snapshot of a company’s finances (what it owns and owes) as of the publication date.

- The balance sheet adheres to an equation that equates assets with the sum of liabilities and shareholder equity.

- Fundamental analysts use balance sheets to calculate financial ratios.

How Balance Sheets Work

The balance sheet provides an overview of a company’s finances at the moment in time. It cannot give a sense of the trends playing out over an extended period. For this reason, the balance sheet should be compared with those of previous periods.1

Investors can get a sense of a company’s financial well-being by using several ratios derived from a balance sheet, including the debt-to-equity ratio and the acid-test ratio, along with many others. The income statement and statement of cash flows also provide valuable context for assessing a company’s finances, as do any notes or addenda in an earnings report that might refer back to the balance sheet.1

The balance sheet adheres to the following accounting equation, with assets on one side and liabilities plus shareholder equity on the other, balance out:

Assets=Liabilities+Shareholders’ EquityAssets=Liabilities+Shareholders’ Equity

This formula is intuitive. That’s because a company has to pay for all the things it owns (assets) by either borrowing money (taking on liabilities) or taking it from investors (issuing shareholder equity).

If a company takes out a five-year, $4,000 loan from a bank, its assets (specifically, the cash account) will increase by $4,000. Its liabilities (specifically, the long-term debt account) will also increase by $4,000, balancing the two sides of the equation. If the company takes $8,000 from investors, its assets will increase by that amount, as will its shareholder equity. All revenues the company generates more than its expenses will go into the shareholder equity account. These revenues will be balanced on the assets side, appearing as cash, investments, inventory, or other assets.

Balance sheets should also be compared with those of other businesses in the same industry since different industries have unique approaches to financing.

Balance sheets should also be compared with those of other businesses in the same industry since different industries have unique approaches to financing.

Special Considerations

As noted above, you can find information about assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity on a company’s balance sheet. The assets should always equal the liabilities and shareholder equity. This means that the balance sheet should always balance, hence the name. If they don’t balance, some problems may occur, including incorrect or misplaced data, inventory or exchange rate errors, or miscalculations.1

Each category consists of several smaller accounts that break down the specifics of a company’s finances. These accounts vary widely by industry, and the same terms can have different implications depending on the nature of the business. But there are a few standard components investors will likely come across.

Components of a Balance Sheet

Assets

Accounts within this segment are listed from top to bottom in order of their liquidity. This is the ease with which they can be converted into cash. They are divided into current assets, which can be converted to cash in one year or less, and non-current or long-term assets, which cannot.

Here is the general order of accounts within current assets:

- Cash and cash equivalents are the most liquid assets, including Treasury bills, short-term certificates of deposit, and hard currency.

- Marketable securities are equity and debt securities for a liquid market.

- Accounts receivable (AR) refers to money that customers owe the company. This may include an allowance for doubtful accounts, as some customers may not pay what they owe.

- Inventory refers to any goods available for sale, valued at a lower cost or market price.

- Prepaid expenses represent the value already paid for, such as insurance, advertising contracts, or rent.

Long-term assets include the following:

- Long-term investments are securities that will not or cannot be liquidated in the next year.

- Fixed assets include land, machinery, equipment, buildings, and other durable, generally capital-intensive assets.

- Intangible assets include non-physical (but still valuable) assets such as intellectual property and goodwill. These assets are generally only listed on the balance sheet if they are acquired rather than developed in-house. Their value may thus be wildly understated (by not including a globally recognized logo, for example) or as wildly overstated.

Liabilities

A liability is any money a company owes to outside parties, from bills it has to pay to suppliers to interest on bonds issued to creditors to rent, utilities, and salaries. Current liabilities are due within one year and are listed in order of their due date. Long-term liabilities, however, are unpaid at any point after one year.

Current liabilities accounts might include:

- The current portion of long-term debt is the portion of long-term debt due within the next 12 months. For example, if a company has a 10 years left on a loan to pay for its warehouse, 1 year is a current liability and 9 years is a long-term liability.

- Interest payable is accumulated interest owed, often due as part of a past-due obligation such as late remittance on property taxes.

- Wages payable is salaries, wages, and benefits to employees, often for the most recent pay period.

- Customer prepayments are money a customer receives before the service has been provided or the product delivered. The company must (a) provide that good or service or (b) return the customer’s money.

- Dividends payable is dividends that have been authorized for payment but have not yet been issued.

- Earned and unearned premiums are similar to prepayments in that a company has received money upfront, has not yet executed its portion of an agreement, and must return unearned cash if they fail to perform.

- Accounts payable is often the most common current liability. Accounts payable is debt obligations on invoices processed as part of the operation of a business that is often due within 30 days of receipt.

Long-term liabilities can include:

- Long-term debt includes any interest and principal on bonds issued

- Pension fund liability refers to the money a company is required to pay into its employees’ retirement accounts

- Deferred tax liability is the amount of taxes accrued but not paid for another year. Besides timing, this figure reconciles differences between requirements for financial reporting and how tax is assessed, such as depreciation calculations.

Some liabilities are considered off the balance sheet, meaning they do not appear on the balance sheet.

Shareholder Equity

Shareholder equity is the money attributable to the owners of a business or its shareholders. It is also known as net assets since it is equivalent to the total assets of a company minus its liabilities or the debt it owes to non-shareholders.

Retained earnings are the net earnings a company either reinvests in the business or uses to pay off debt. The remaining amount is distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends.

Treasury stock is the stock a company has repurchased. It can be sold later to raise cash or reserved to repel a hostile takeover.

Some companies issue preferred stock, which will be listed separately from common stock under this section. Preferred stock is assigned an arbitrary par value (as is common stock, in some cases) that has no bearing on the market value of the shares. The common stock and preferred stock accounts are calculated by multiplying the par value by the number of shares issued.

Additional paid-in capital or capital surplus represents the amount shareholders have invested more than the common or preferred stock accounts, which are based on par value rather than market price. Shareholder equity is not directly related to a company’s market capitalization. The latter is based on the current price of a stock, while paid-in capital is the sum of the equity that has been purchased at any price.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Par value is often just a minimal amount, such as $0.01.2

Importance of a Balance Sheet

Regardless of the size of a company or industry in which it operates, there are many benefits of a balance sheet,

Balance sheets determine risk. This financial statement lists everything a company owns and all of its debt. A company can quickly assess whether it has borrowed too much money, its assets are not liquid enough, or has enough cash to meet current demands.

Balance sheets are also used to secure capital. A company usually must provide a balance sheet to a lender to secure a business loan. A company must also typically offer a balance sheet to private investors when attempting to secure private equity funding. In both cases, the external party wants to assess a company’s financial health, the business’s creditworthiness, and whether the company can repay its short-term debts.

Managers can use financial ratios to measure a company’s liquidity, profitability, solvency, and cadence (turnover) using financial ratios, and some financial ratios need numbers taken from the balance sheet. When analyzed over time or compared against competing companies, managers can better understand ways to improve a company’s financial health.

Last, balance sheets can lure and retain talent. Employees usually prefer knowing their jobs are secure and that the company they are working for is in good health. For public companies that must disclose their balance sheet, this requirement gives employees a chance to review how much cash the company has on hand, whether the company is making intelligent decisions when managing debt, and whether they feel the company’s financial health is in line with what they expect from their employer.

Limitations of a Balance Sheet

Although the balance sheet is invaluable for investors and analysts, some drawbacks exist. Because it is static, many financial ratios draw on data included in the balance sheet and the more dynamic income statement and statement of cash flows to paint a fuller picture of what’s happening with a company’s business. For this reason, a balance alone may not paint the complete picture of a company’s financial health.

A balance sheet is limited due to its narrow scope of timing. The financial statement only captures a company’s financial position on a specific day. Looking at a single balance sheet by itself may make it challenging to extract whether a company is performing well. For example, imagine a company reports $1,000,000 of cash on hand at the end of the month. Without context, a comparative point, knowledge of its previous cash balance, and an understanding of industry operating demands knowing how much cash on hand a company has yielded limited value.

Different accounting systems and ways of dealing with depreciation and inventories will also change the figures posted on a balance sheet. Because of this, managers have some ability to game the numbers to look more favorable. Please pay attention to the balance sheet’s footnotes to determine which systems are being used in their accounting and to look out for red flags.

Last, a balance sheet is subject to several areas of professional judgment that may materially impact the report. For example, accounts receivable must be continually assessed for impairment and adjusted to reflect potential uncollectible accounts. Without knowing which receivables a company will likely receive, it must make estimates and reflect its best guess as part of the balance sheet.

Example of a Balance Sheet

The image below is an example of a comparative balance sheet of Apple, Inc. This balance sheet compares the company’s financial position as of September 2020 to the company’s financial position from the year prior.

In this example, Apple’s total assets of $323.8 billion is segregated toward the top of the report. This asset section is broken into current and non-current assets, and each category is split into more specific accounts. A brief review of Apple’s assets shows that their cash on hand decreased, yet their non-current assets increased.

This balance sheet also reports Apple’s liabilities and equity, each with its section in the lower half of the report. The liabilities section is broken out similarly to the assets section, with current liabilities and non-current liabilities reporting balances by account. The total shareholder’s equity section says the common stock value, retained earnings and accumulated other comprehensive income. Apple’s total liabilities increased, equity decreased, and the combination of the two reconciled to the company’s total assets.

Why Is a Balance Sheet Important?

A balance sheet is an essential tool used by executives, investors, analysts, and regulators to understand the current financial health of a business. It is generally used alongside the two other types of financial statements: income and cash flow statements.

Balance sheets allow the user to get an at-a-glance view of the assets and liabilities of the company. The balance sheet can help users answer questions such as whether the company has a positive net worth, has enough cash and short-term assets to cover its obligations, and is highly indebted relative to its peers.

What Is Included in the Balance Sheet?

The balance sheet includes information about a company’s assets and liabilities. Depending on the company, this might consist of short-term assets, such as cash and accounts receivable, or long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). Likewise, its liabilities may include short-term obligations such as accounts payable and wages payable or long-term liabilities such as bank loans and other debt obligations.

Who Prepares the Balance Sheet?

Depending on the company, different parties may be responsible for preparing the balance sheet. The owner or a company bookkeeper might prepare the balance sheet for small privately-held businesses. Mid-size private firms might be prepared internally and reviewed by an external accountant.

On the other hand, public companies must obtain external audits by public accountants and ensure their books are kept to a much higher standard. These companies’ balance sheets and other financial statements must be prepared under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). They must be filed regularly with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).3

What Are the Uses of a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet explains the financial position of a company at a specific point in time. As opposed to an income statement which reports financial information over some time, a balance sheet is used to determine the health of a company on a specific day.

A bank statement is often used by parties outside a company to gauge the company’s health. Banks, lenders, and other institutions may calculate financial ratios off the balance sheet balances to gauge how much risk a company carries, how liquid its assets are, and how likely the company will remain solvent.

A company can use its balance sheet to craft internal decisions, though the information presented is usually less helpful than an income statement. A company may look at its balance sheet to measure risk, make sure it has enough cash on hand, and evaluate how it wants to raise more capital (through debt or equity).

What Is the Balance Sheet Formula?

A balance sheet is calculated by balancing a company’s assets with its liabilities and equity. The formula is total assets = total liabilities + total equity.

Total assets are calculated as the sum of all short-term, long-term, and other assets. Total liabilities are calculated as the sum of all short-term, long-term, and other liabilities. Total equity is calculated as the sum of net income, retained earnings, owner contributions, and shares of stock issued.

- Harvard Business School Online. “How to Prepare a Balance Sheet: 5 Steps for Beginners.”

- Cambridge Dictionary. “Par Value.”

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “Standard Taxonomies.”